Sitting on a wall outside St. Augustine’s monastery, on what’s the highest point in the city, Nassau. I’m facing north, and the sun’s not too hot, both because it’s only 8:30 A.M. and because there’s a right nice cloud cover. A very pleasant breeze at my back. The hilltop seems to catch breezes. We walked last night, and the whole area was cool and breezy.

Benedictus montes amavit, Bernardus valles.

We spent yesterday getting acclimated. Arrived at about 1 P.M. and Steve’s great uncle George Wolf picked us up. He’s a “typical” German male from Minnesota—very interested in being in control. The other monks, particularly the younger ones, have said as much. Food for thought: what’s perhaps ethically appropriate in one generation (the macho masterful control expected of the pioneer/missionary) is

not for the next (post-hippie, post 60s youth). But also food for thought in that the church has yet to understand the sea-changes of the 60s, and much of the conflict I feel is with an institution will dominated by those who think à la macho pioneer/missionary. John Paul II as a reasserter of threatened masculinity, Paul VI as sensitive feminine.

Anyway, the Bahamas. The soil is rocky and thin, and the vegetation—especially here, on this dry hilltop—surprisingly desert-like. There’s a plant I know only as Moses-in-the-basket, a sedum-like plant with fleshy leaves, long and tapered, purple beneath and green above. Is it called

Rhoeo spathacea? For some reason, that name sticks in my mind.

There’s aloe vera and cactus, but are these native, or did the monks plant them? An aloe I looked at last night had two brown lizards with sharply pointed tails a-rest on its leaves, as if they were cushions.

Fr. George pointed out a red-flowering tree called Poinciana. It, too, is desert-like: rises to an umbrella shape, with a bare shapely trunk something like crepe myrtle. The flowers are cup-shaped but frilly, in stiff up-pointed brackets. Why do I think of it as euphorbia—

E. resplendens? I must break a branch and see if it’s milky.

And, of course, there’s croton, chenille plant (both grown as shrubs), lovely purple and magenta bougainvillea, which is grown both as a vine and a shrub, Confederate jasmine, Mexican coral vine. There’s a tree just beginning to bloom, which George calls showers of gold—showy yellow clusters of bloom—and there’s a tree with white blossoms that’s just stopping blooming, called Bohemia.

In the midst of this, third-world chaos and decay. The monastery typifies this. It’s a huge complex of buildings, most of which were never completed and, most appropriate of all, the church itself never finished. All built in the 40s when Catholicism seemed serenely triumphant, stable,

semper virens et vivens, and vocations were flocking.

And yet: the buildings are now almost empty, almost bereft of humanity, except for aging monks of the macho pioneer/missionary variety, who lived in bemused isolation as the world they inhabited and built falls apart around them.

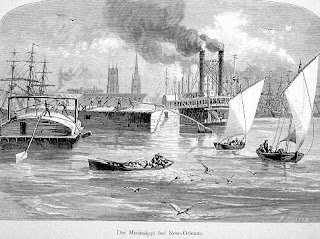

George Wolf says when he came to Nassau in 1944 the population was 24,000. Today, it’s 175,000. As one drives through the neighborhoods of the city, which is (as with the island itself) 90% black, one sees shanty after shanty, doors open, tattered lace curtains at the only window, debris on the street everywhere, men gathered on stoops of liquor stores. It could be New Orleans.

The church lives uneasily in this society. Vatican II troubled its untroubled complicity with imperialism. A history of Bahamian Catholicism Before lent us,

Upon These Rocks, by Coleman Barry—is full of pictures of monks with British royalty, monks with British governors, monks with Clare Booth Luce, monks with white people, happy black people with baskets of pineapple on their heads.

And, boom, Vatican II, exodus of monks and nuns in droves, empty white palaces atop hills, teeming colored populations down below in slums. The younger monks are all reading Donald Goergen’s

Sexual Celibate. Though most are now black or Indian (from Trinidad), with the exception of young white monks sent in from St. John’s, the “native” vocations go up to St. John’s for study and novitiate, and come back talking about how beer in the Bahamas costs $3 bucks a bottle.

O my people, what have I done to you, in what have I offended you? Answer me. The

novum never comes except with death, decay, struggle. . . .

+ + + + +

Lying on beach on Paradise Island, full sun, mid-afternoon. The sky is lovely, full of cumulus clouds, but still deep blue, and the water—indescribably clear, blue green. A young woman to my right is shamelessly topless, a German (?) gay couple, one with long blond curly hair, the other with slicked back dark hair, in the water ahead of us. Not bottomless, sadly.

+ + + + +

Back at St. Augustine’s, reading Rilke’s

Stories of God, which are full of wonderful Rilkean apercus, but are on the whole strange to me. Not because

they’re strange, but I’m reading out of duty and not delight.

Perhaps appropriately, thinking of mystery, and especially how American Catholics so quantify and oppress things into one shape alone that they have no sense of people’s mysterious depths.

Sent Joe M. a birthday card today, with the El Dorado poem I’ve tried desultorily to finish in this journal, and can’t. . . . I can’t get it right: it’s a poem re: loss of innocence, love, youth.

In Montréal, watching steam (or is it smoke?) waft lazily out of chimneys in Snowdon on a rather cold (-20◦) morning. We’re in the 20th-story apartment of G. and S. Baum.

In Montréal, watching steam (or is it smoke?) waft lazily out of chimneys in Snowdon on a rather cold (-20◦) morning. We’re in the 20th-story apartment of G. and S. Baum.